The Quest and the Endurance: tales of Antarctic heroism

An upcoming biopic of Sir Ernest Shackleton, featuring Tom Hardy, is set to build on the great explorer's legend

I recall a friend once describing the frigidity of a biting Scottish winter’s day in dramatic terms.

“It was so cold, Ernest Shackleton would’ve gone home to put on the telly,” he said.

The line worked because everyone knows that Sir Ernest Shackleton was an Antarctic explorer.

But beyond that…..?

Growing up in the 1970s, it was his contemporary Robert Falcon Scott, and his race to the South Pole with the Norwegian Roald Amundsen (which he lost) that hogged the imagination of a child like me, who devoured Ladybird illustrated history books.

Yet, this week in Dundee, Scotland, there is a Festival of Shackleton to celebrate the 150th anniversary of his birth.

That the City of Discovery (so-called because it built and is now host to Scott’s ship Discovery) is focusing on Shackleton, rather than Scott, points to a shift in public attitudes toward the two men.

Shackleton’s connections with Dundee and Scotland are strong - he was third officer on Scott’s Discovery Expedition to Antarctica in 1901-04 and even ran for Parliament in the city in 1906. Between expeditions, he was also the secretary of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

But that doesn’t explain the revisionism that is taking place.

Scott is now viewed as a typical Edwardian-era man of his time, while Shackleton is increasingly seen as an exceptional figure who put the welfare of his men ahead of his own ego; a model of modern-day leadership.

The reappraisal of Shackleton’s place in history will no doubt be spurred by an upcoming biopic that is scheduled to star Tom Hardy as the great man.

A quote from the movie’s producer, Dean Baker, hints at why his star is rising. “Tom and I were always fascinated by Shackleton as a leader, by his contagious optimism and by his absolute belief in his team,” Baker said. “At a time where leaders seem to be more about self than society, Shackleton sacrificed his own needs to ensure the wellbeing of his team – that’s inspirational.”

I spoke about Shackleton with John Geiger, an old friend and colleague, who is chief executive officer of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society and who was in Dundee to give the keynote address about the Canadian connections to the explorer.

Last June, Geiger led an expedition in the Labrador Sea, off Canada’s East Coast, to look for Quest, the ship on which Shackleton died in 1922.

After Shackleton’s death at the age of 47, Quest was sold to Norwegian owners and converted into a seal-hunting ship. It sank in 1962 and settled in 1,300 feet of water, undiscovered until Geiger’s team found it last June. More of which later.

Shackleton’s death aboard Quest en route to Antarctica, is seen as the end of the Heroic Age of Antarctic expedition that included Scott’s voyages aboard Discovery and Terra Nova, as well as Shackleton’s three expeditions aboard Nimrod (1907-09), Endurance (1914-17) and Quest (1921-22).

None of his voyages achieved their primary objective but few would associate Shackleton with the plucky loser stereotype, such are the tales of heroism and sacrifice.

Geiger said that the Nimrod expedition could have reached the South Pole, immortalizing Shackleton as the first human to lead a party there.

“But he turned back because he knew that if he continued he would lose, if not his entire party, at least a couple of his men. That was a real sign of the character of the man. He was very unusual for his day,” he said.

That trek proved to be a race to avoid starvation. Shackleton’s team were restricted to half-rations and at one point, Shackleton gave his one biscuit of the day to an ailing colleague. “All the money that was ever minted would not have bought that biscuit, and the remembrance of that sacrifice will never leave me,” he noted later.

“I think that his deep humanity is part of why he has become a globally important figure,” said Geiger.

The reputation, established on the Nimrod expedition, was cemented by the Trans-Antarctic exploration of 1914-17. After Amundsen had conquered the South Pole in 1912, Shackleton turned his attention to crossing the continent from sea to sea, via the pole.

He led an expedition of two ships, Endurance and Aurora, the latter of which would land large supply depots on the other side of Antarctica. The expedition was sponsored by Dundee jute magnate, Sir James Caird.

However, its fate was sealed when Endurance became stuck in pack ice and had to be abandoned before it sank in November, 1915.

The 28 men aboard escaped by camping on the ice for two months, living off penguins, seals and seaweed, before taking to sea in three lifeboats.

After five days in extremely rough waters, they landed on Elephant Island, 346 miles from where Endurance sank.

Another mark of Shackleton’s leadership in extreme circumstances is that he gave his mittens to photographer Frank Hurley, who had lost his own. Shackleton suffered frostbite on his fingers as a result.

With rescue unlikely, Shackleton and five others risked an open boat journey aboard the James Caird lifeboat, to attempt to reach the whaling station at South Georgia. They left on April 24th, 1916, reaching the south side of the island of South Georgia on May 8th. They then had to trek 32 miles over inhospitable terrain to reach the whaling station on the north coast, which they did on May 20th.

A Chilean naval ship and a British whaler eventually reached Elephant Island on August 30th and all hands were rescued. They were taken to Chile, after which Shackleton travelled to New Zealand to join Aurora, which had fared less well, losing three men including its captain, Aeneas Mackintosh.

Shackleton spent much of the following five years on speaking tours, one of which took him to Canada, where the idea of an Arctic expedition to explore a potentially undiscovered land mass in the Beaufort Sea was mooted. Shackleton bought Quest, hired a crew, secured provisions and even found a sponsor in the Eaton family, which committed $100,000 (the equivalent of $1.7 million today).

“There are references in his papers to the North Pole and making a dash for the pole could have been feasible,” said Geiger. “It’s an exciting ‘what if’ of history.” (Two Americans, Frederick Cook, and Robert Peary, claimed to have reach the pole by land in 1908 and 1909 respectively but doubts about the accuracy of their claims have emerged. The first verified land mission was a 24-man Soviet party in 1948).

Shackleton was enamoured with Canada and spoke about the country being part of his future. Unfortunately, Canada did not return the affection and, at the last moment, the government of Arthur Meighen withdrew its support for the expedition.

Shackleton was faced with a situation where he had a provisioned boat and crew lined up but no mission. He subsequently raised funds from an old friend, John Quiller Rowett and conceived the Shackleton-Rowett expedition to circumnavigate the Antarctic.

Quest left London on September 17th, 1921, on what Shackleton described as his “swan song”. He was cheered off by thousands, including King George V, but he never achieved his objective.

The great explorer died of a heart attack in South Georgia - the only death to take place on any of the ships under his direct command.

Quest was then subsequently sold to Norwegian owners as a sealer and sank in 1962, after being damaged by ice while on a seal hunt.

Geiger explained his motivation for what he called “a feat of detective work” - finding Quest’s final resting place.

“Quest was, to me, a link to this whole story, a way to tell this story, a way to excite Canadian interest in our geography but also in our history,” he said.

Earlier this year, he set off with a team of Canadian, American, British and Norwegian oceanographers and historians, including lead researcher Antoine Normandin and American shipwreck hunter, David Mearns.

Mearns summed up the impetus for such deep water searches. “It’s not the ship, it’s the people who were in the ship,” he said. The shipwreck is a platform for telling their stories.

(The Royal Canadian Geographical Society expedition to find Quest - CEO John Geiger is fourth from left, back row. Antoine Normandin is third from left at the front and David Mearns is fourth from left, front).

The team had the final position of Quest, sent by the Norwegian captain before he abandoned ship in 1962. But it proved to be off by several miles and it took a combination of consulting old ships’ logs, newspaper clippings, legal documents and historic weather and ice data to determine Quest’s final resting place using sonar towfish.

Geiger described the moment of discovery as “profoundly moving” .

(An excellent first hand account of the search is provided here by RCGS’s Alexandra Pope).

Geiger says the RCGS plans to return to the site with a remote operated vehicle, and perhaps even a submarine, to take a closer look at Quest, with the hope of creating a digital twin of the ship.

Many people reading this might wonder at all this fuss over a man who, ultimately, failed.

But Shackleton’s story is comparable to the space race in later decades.

It might seem like an empty gesture to go to the South Pole, or the moon, only to turn around and come back.

But those quests into the unknown are the very essence of adventure, courage and endurance that continue to fascinate.

“I think these stories of individual heroism, the sacrifice, the romance of discovery on a planet that is much busier and more densely populated…there is an enormous explosion of interest,” said Geiger.

He said 1,200 people gathered in Dundee’s Caird Hall this week (named after Shackleton’s sponsor) and it was suggested that if you’d asked people to raise their hands if they’d been to either South Georgia, where the explorer is buried, or Antarctica, a surprising number of people would have done so.

“Part of that is on the coat-tails of Shackleton’s celebrity. I think he has in a way become the focus and Scott has been kind of forgotten to a certain extent,” said Geiger

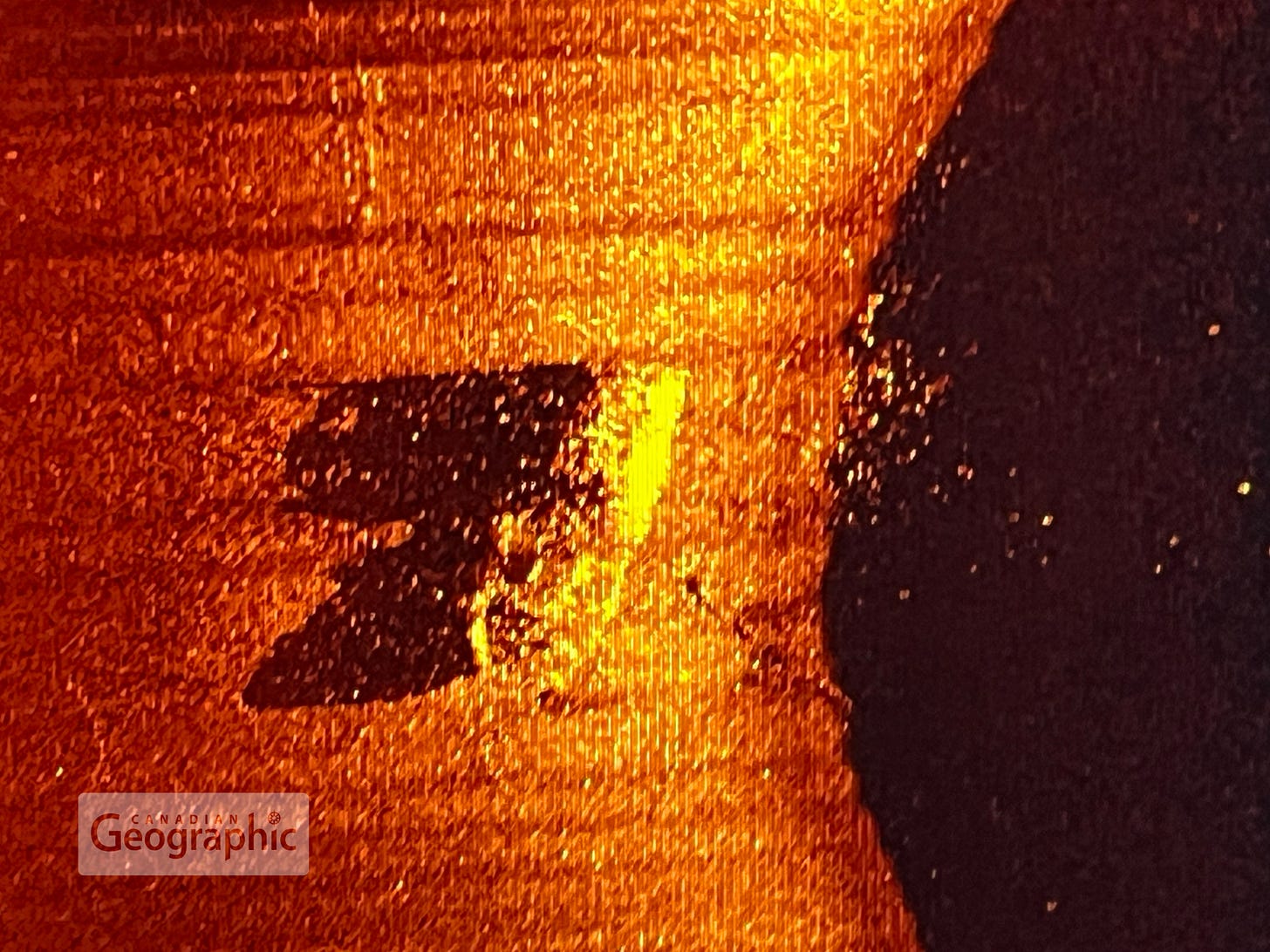

(The sonar image of Quest - all photographs courtesy of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society).

.

Curiously, I learned at my boarding school in England of Shackleton’s exploits (I was about ten years old). It wasn’t until I attended a nautical training school, three or four years later, that Scott’s expedition was mentioned.

That my boarding school history teacher was a Scot probably had something to do with it.

Shackleton’s story is fascinating. I had the good fortune to go to Antarctica with OneOcean prior to lockdown. Said a prayer at his grave site. Walked in his footsteps on South Georgia Island, memorable. So memorable that it is my profile pic.