Forgetting Manchester United

l've fallen out of love with a club that has forgotten its sense of place and lost its soul

When Fly Straight launched on an unsuspecting world late last year - or more accurately, emerged bleary of eye and tousled of hair - I said I wanted to build a little community capable of holding conversations about politics, the social zeitgeist and economics. I even said I’d comment on sport, in other words, football (or soccer, if we must).

So far, I have used this platform to discuss many things, from shoes, ships and sealing wax, to cabbages and kings. But never football, until now.

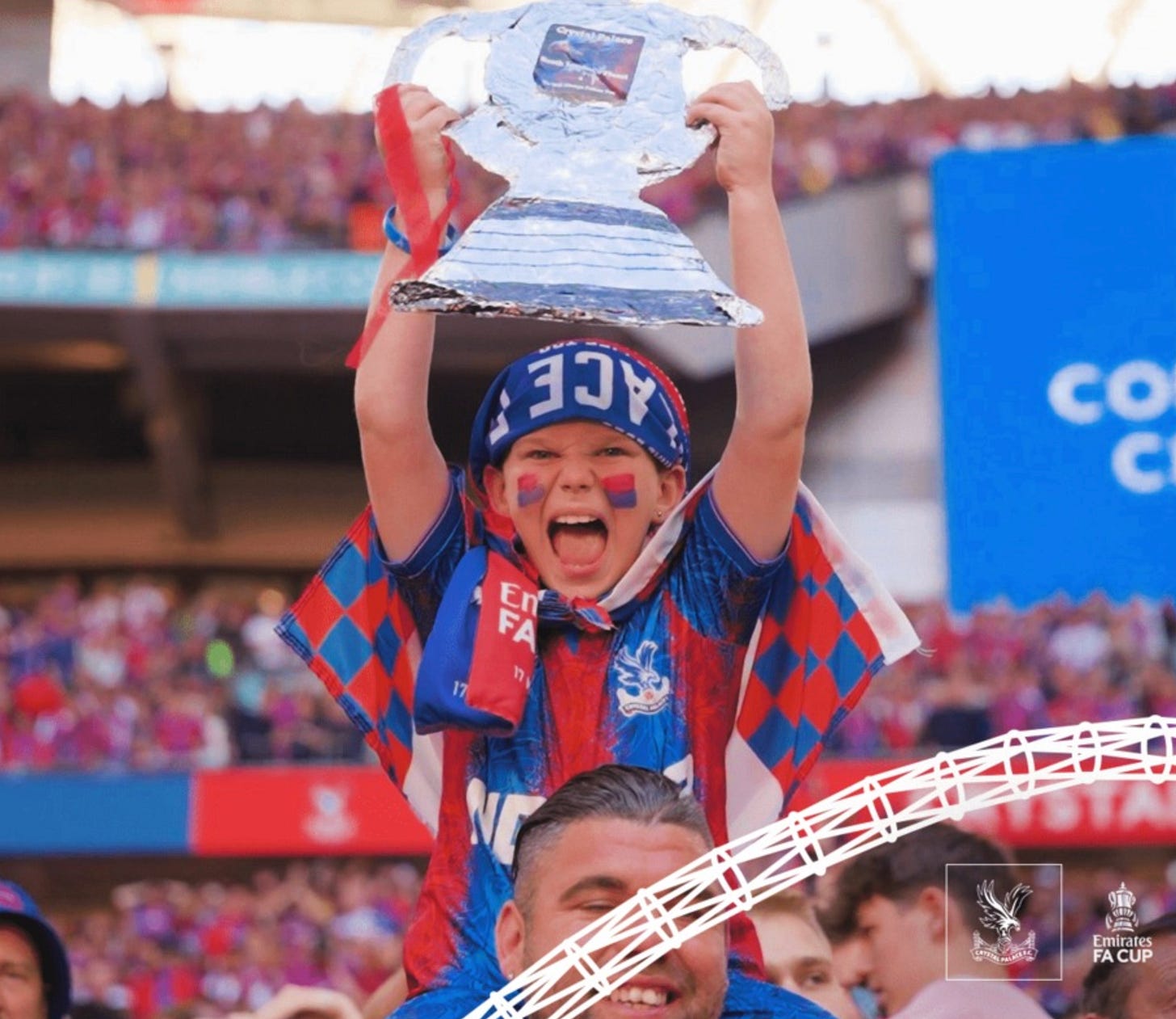

I am moved to do so by two short videos on social media - one was of a father hugging his son after relative paupers Crystal Palace beat heavily-favoured Manchester City, in the F.A. Cup Final to win its first ever trophy. The boy is sobbing his heart out, while his father holds him tight - an act of pure emotion neither will ever forget. Palace are from South London - a proper club, with proper fans who are considered among the most passionate and noisiest in English football.

The other was the desultory sight of Manchester United players on an open top bus parade through the streets of Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, having lost a friendly match to ASEAN All-stars, an exhibition side of Asian internationals. The loudspeaker played “Glory, Glory Man United” on a loop but has not been much to celebrate for United this season, having lost the Europa League final to Spurs and ending up 15th in the English Premier League, their worst finish in 50 years. That was reflected in the listlessness of the whole affair on the part of players and fans, both of whom recognized the trip east for what it is - a crass cash grab.

United are a side unrecognizable from the team I have supported my whole life - a club without identity, direction or soul.

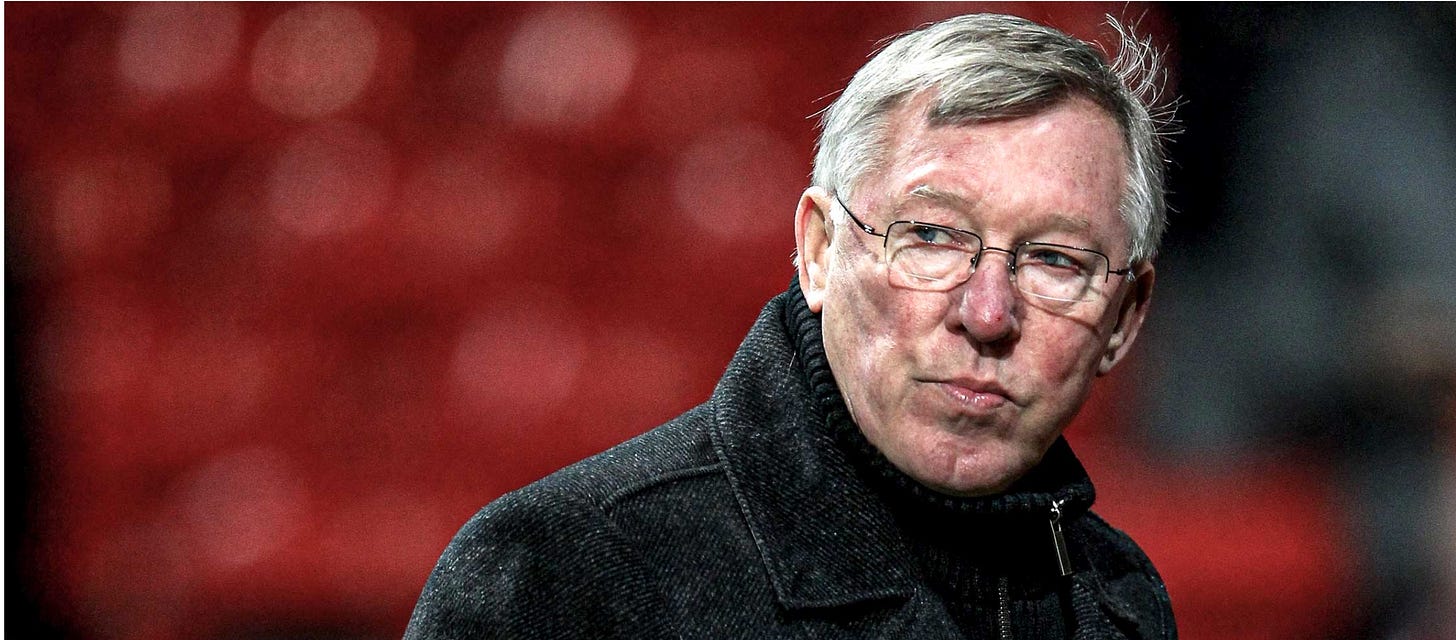

My dad’s brother and sisters moved to Manchester from Scotland after the war and I was taken to Old Trafford to watch teams packed with legends like my hero Martin Buchan, one of the club’s great captains. The team was relegated in 1974 but it was still recognizably the club of Matt Busby’s “babes”; the team of Denis Law, Bobby Charlton and George Best that was rebuilt after the 1958 Munich air disaster that killed eight players. There was a direct line between the two great Scotsmen who made the club iconic - Busby and Alex Ferguson, whose teams dominated British and European football over the course of 26 years, including 13 Premier League titles and two Champions League cups.

Fergie must consider what has befallen his beloved United since his retirement in 2013 to be sacrilege - and so do I.

His success was built on a team-first mentality, where individual talents were subservient to the collective goal of winning. Egos were not long tolerated, as David Beckham found out the hard way. “The work of a team should always embrace a great player but the great player must always work,” he said.

Fergie’s (and Busby’s) United were built on discipline, loyalty and leadership. Players were taught resilience in the face of defeat.

Contrast that with today. The current squad of pampered mercenaries are as resilient as soap bubbles.

Witnessing United play these days is as much fun as watching a potato bake.

But this is not meant as a digression into Generation Z’s lack of emotional fortitude. It is a criticism of the loss of connection to place.

United nurtured Scott McTominay from the age of five years old. He was born nearby in Lancaster, although he qualified to play for Scotland through his Scottish father. He was highly regarded by every coach he had, including Jose Mourinho, and was steeped in Fergie’s ethos about discipline, loyalty and hard work. He was strong, talented and a natural leader. But he was consistently played out of position and regarded as a “squad” player by the fans and media (that is, not in the starting 11). In a move typical of the short-sighted recruitment policies at United, he was sold to Napoli last August. It was the worst business decision since New Coke. Last week, McTominay scored the winning goal that allowed Napoli to win the Scudetto, as Italian league champions, and he was named the Serie A player of the season.

The backdrop to all of this is the toxic culture introduced by United’s owners, the American Glazer family, who bought the club via a leveraged buy-out in 2005, securing the loans against United’s assets. As a result, the club was saddled with massive debts, while the Glazers syphoned money out through dividend payments. Meanwhile, the board ignored the fact that Old Trafford, the “Theatre of Dreams”, was falling into disrepair and a revolving door of managers were buying players who did not measure up to Fergie’s standards. No wonder fans like me feel betrayed.

Bill Shankly, another legendary Scottish manager, once disputed the idea that football is a matter of life and death. “I don’t like that attitude. I can assure you that it is much more serious than that.”

That may be exaggerating just a little. But it is about life and death; and place and family.

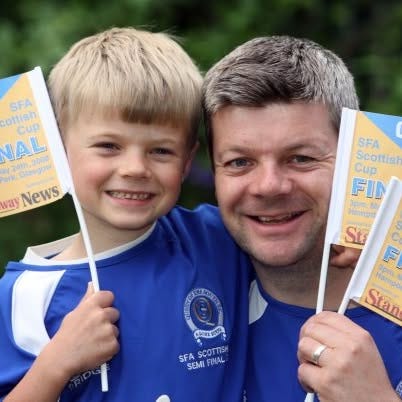

I can still conjure up the sights and smells of stale meat pies and Bovril, served in a canteen full of large men and industrial language, at half-time at Palmerston Park, Dumfries, where my late father took me every week to watch our local heroes, Queen of the South.

It was a regular pilgrimage during the Wilderness Years (1919 to 2008) and it was only after his death that they had a shot of glory in the Scottish Cup Final at Hampden Park against the (then) mighty Glasgow Rangers, where they lost by the odd goal on a glorious sunny afternoon. I travelled back from Canada to go to the game with my own six year old son, wearing our Queens’ jerseys with pride, just as I had half a lifetime before with my own Dad.

I have been very fortunate in life to live and work in Glasgow, Toronto, Ottawa and now San José. But Dumfries is my anchor - the home of Robert Burns and the Queens.

Football is Dumfries, my Dad is football and Dumfries is my Dad. They are tightly interwoven in my emotional psyche - the traditions, the nostalgia, the elation and the despair.

That’s football. You don’t have to be from the green half of Edinburgh to get a lump in your throat when thousands of Hibernian fans belt out Sunshine on Leith.

As in politics, when football loses its connection to place, it ceases to carry any meaning.

Proponents of proportional representation argue we should follow countries like the Netherlands that have eschewed constituencies, in favour of a nationwide allocation of seats from party lists.

But all politics, like football, is local.

The reality of life in the town and communities that sustain these clubs is divorced from the superabundance their overpaid stars enjoy (United’s top earner, the Brazilian Casemiro, reportedly earns nearly 500 times the U.K. median wage).

I retain a deep love for the Queens. They come from the place that made me.

When it comes to United though, I am like a spurned lover - I feel bitterness, anger and resentment that they have thrown away what we once had. Being a fan is deeply personal and requires a sense of collective identity. But I don’t identify with this club anymore.

That’s why I relished the sight of that young Crystal Palace fan, in floods of tears, hugging his dad. Manchester City, financed by UAE’s Sheikh Mansour, were odds-on favourites to win the final. But money has not managed to ruin the beautiful game entirely. Despite City’s early dominance, striker Eberechi Eze scored a fine volley, while goalkeeper Dean Henderson’s heroics, including a penalty save, allowed Palace to hang on.

No wonder it produced such scenes of unbridled joy.

That’s the essence of the game - fathers, sons and football, celebrating one of the biggest moments of their lives together.

As Fergie once said (after his side scored two goals in injury time to beat Bayern Munich in the 1999 Champions League final): “I can't believe it. I can't believe it. Football. Bloody hell.”

Football, to me, is the NFL and CFL. But I understand your passion. Your point about the corporate soullessness of the team rings true for me with hockey. Despite living in Toronto my entire adult life and growing up in a family of Leafs fans, I could never love that team. I only understood why as an adult: first Harold Ballard, and then the corporate, soulless entity that they have become. Blechhh. So, from 9 years old and going forward, I am a diehard New York Islanders fan (NHL) and Philadelphia Eagles fan (NFL) -- and of course I am, being from Cape Breton Island (ahem, "Islanders") and having the family name Eagles. :)

But, truly, I am an Islanders fan because of one legendary player: Denis Potvin. When the Isles drafted him, that made my decision for me.

All the best, John. I hope your team is once again able to imbue you with hope and joy in the near future.

A lifelong Spurs supporter (I first went to White Hart Lane as an eight-year-old in 1960) I especially relished their win over ManU in the Europa League cup final. It was Tottenham’s first trophy in seventeen years and it came at the end of a particularly disappointing league season; we actually finished below United!

But I also often yearn for those far off days when the top-level players were still nonetheless relatable to the average fan. Today’s pampered millionaires sometimes make it difficult to cheer for them. The world moves on . . .