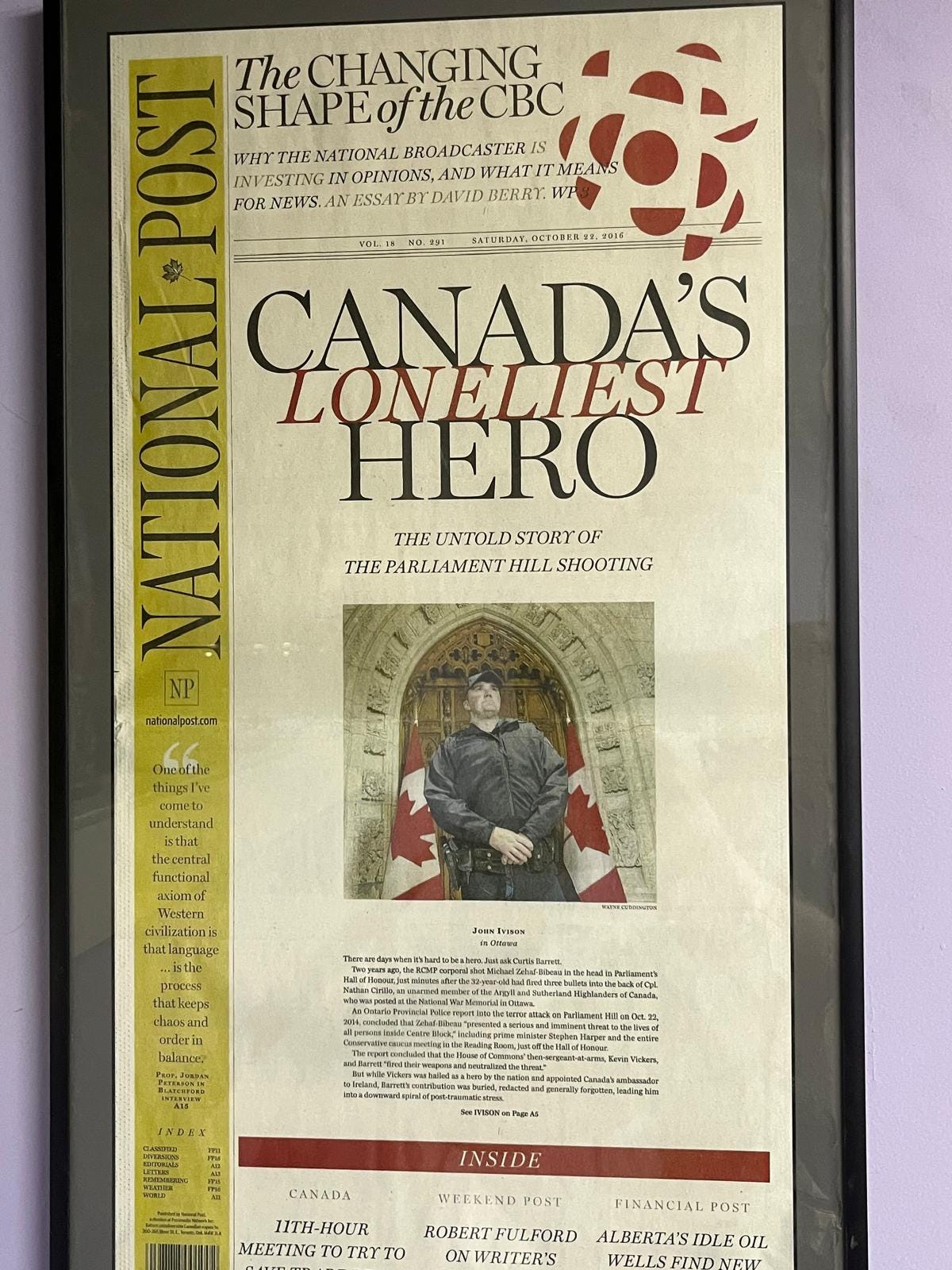

Canada's loneliest hero is now Canada's forgotten hero

On the 10th anniversary of the attack on Parliament Hill, we should celebrate the actions of Curtis Barrett and Kevin Vickers

John Ivison

We are approaching the first anniversary of Hamas’ terror attack on Israel, an atrocity that many Canadians seem to have erased from their memories as they protest the Jewish state’s right to defend itself.

Canada seems so far removed from the horrors of the Middle East that it is easy to forget that Islamic terrorism struck at the hearth of this country’s democracy 10 years ago this month.

The morning of Wednesday, October 22nd 2014 began like any other pleasant fall day in Ottawa, safe and tranquil. I was about to deliver a speech to a corporate audience five minutes from Parliament Hill, alongside broadcaster Evan Solomon, when our Blackberries started buzzing: a friend whose office overlooked the War Memorial said he’d just witnessed the shooting of one of the two ceremonial guards. Solomon and I rushed to the Cenotaph, where he took the picture that appears here of the fallen figure of Corporal Nathan Cirillo, a reservist from Hamilton, Ont. My friend said he’d seen a gunman pump three shots into Cirillo’s back. “He had a black and white Palestinian type head scarf over his face that he pulled down after the shooting, then he held up the gun and shouted something I didn’t hear,” he said.

What he shouted was “Allahu akbar”. The gunman was Michael Zehaf-Bibeau, a 32-year-old drug addict of Libyan descent from Montreal. After leaving Cirillo to bleed to death, he raced back to his car, U-turned up Wellington Street, abandoned the car and ran on to Parliament Hill. There, he commandeered a ministerial car, drove to Centre Block and burst into the building, wrestling with a House of Commons security guard, before running towards the Library of Parliament at the north end of the Hall of Honour.

Unbeknownst to him, the weekly Conservative caucus meeting was being chaired by Prime Minister Stephen Harper, in the Reading Room, halfway up the Hall.

Const. Curtis Barrett, a 34-year-old explosives detection officer, was on duty at the vehicle screening facility at the bottom of Parliament Hill when word came through on his walkie-talkie that there was a man with a gun in Centre Block.

He drove to the Peace Tower and formed a diamond-shaped formation, known as an Incident Active Response Deployment (IARD), with three other officers - Sgt. Richard Rozon, Const. Martin Fraser and Cpl. Danny Daigle. The four men walked up the steps of Centre Block and into the Rotunda.

Barrett said at the time he smelt gunpowder and knew shots had been fired.

Moving forward down the Hall of Honour, Barrett saw the House of Commons Sgt-at-Arms, Kevin Vickers, taking cover against a wall.

The team saw movement at the Library of Parliament doors before a gunshot created a shockwave as it passed Barrett.

Zihaf-Bibeau was distracted by the RCMP officers, allowing Vickers to break cover and start shooting. Barrett said he was firing as he walked forward and the combination of firepower ended Zihaf-Bibeau’s brief reign of terror.

An Ontario Provincial Police report into the attack later concluded that the attacker “presented a serious and imminent threat to the lives of all persons inside Centre Block” and that it was a combination of 31 shots from Barrett and Vickers that neutralized the threat.

Vickers later walked into folklore, telling parliamentarians: “I put him down”, even though in his statement on the incident, he referred to the courage of other security personnel and his pride at being part of the team that ended Zihaf-Bibeau’s attack.

The media lapped up the story of the lone hero and the narrative had no room for nuance, such as Barrett’s involvement.

Unequivocally, Vickers is a Canadian hero, who put his life on the line to save others.

But so is Barrett, and his story turned out very differently from the man who was later named Canada’s ambassador to Ireland.

He spent the day with his gun drawn for six hours, guarding the NDP caucus as rumours about another gunman ran down the halls of Parliament.

After he was relieved, he handed in his gun and body armour, was interviewed and driven home. That was his last contact with the RCMP for four days. He attended a debriefing the following week, which he had to leave to throw up. Then he drove to Hamilton for Cirillo’s funeral. When he got home, he found his 10-year-old dog had died. “It was the day after Nathan Cirillo’s funeral and I was digging a hole in the back-yard to bury my dog. I lost my shit for the first time that day,” he said.

The RCMP proved to be ill-equipped at dealing with mental health issues. “My doctor told me that this is what leads to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder - the lack of follow up. This is why we have suicides,” he told me in an interview in 2016.

Barrett’s life went into a downward spiral and he didn’t return to duty for nearly two years.

His relationship with his girlfriend broke up, in part because nobody believed that he had been involved in the shooting given the media narrative that Vickers had single-handedly taken out the terrorist.

Feelings of abandonment were reinforced when, a year after the attack, the RCMP’s Health Services division revealed it had no record of Barrett’s involvement in the shooting.

It wasn’t until he was sent to an operational stress clinic in early 2016 that he started to get his life back together.

I spoke to Barrett again on Friday and he is in a much better place.

He is now a sergeant and the divisional reintegration coordinator for the Ottawa region and Nunavut. It is his job to help RCMP members who have endured their own traumatic events.

He said the RCMP’s response to an incident like the Parliament Hill shooting would be 100 percent better.

“What we do is teach managers our lessons learned, so that officers are not treated like criminals and separated from their peers. Legally, they don’t have to be separated - they can be asked not to discuss something under investigation, but they can still reach out and talk to their colleagues,” he said.

“I was floating in the air, not knowing if I was suspended, being investigated or on leave.”

He said he can help others because he’s “miles ahead of where I was”.

While the Parliament Hill attack still echoes through his life, he has managed to move on.

“I don’t mince words any more. I say that Zihaf-Bibeau was on his feet holding his rifle, that Vickers was out of bullets and that I killed Bibeau. I shot him in the head,” he said. “This is a case study of the first person who gets to the microphone making history.”

Barrett married his wife Laura on Canada Day 2020, in a backyard ceremony in the middle of the pandemic. He said her late father, Terry Pacini, helped him a lot, telling him the RCMP is his employer, not a brotherhood or a calling, and that he needed to draw a line.

For a third generation policeman from Newfoundland, the suggestion that he was expecting too much from the RCMP was a revelation.

Barrett said that he was reminded how close he came to death that day when he had his reintegration class reenact the attack. He set up a hall to resemble the Hall of Honour and had a police officer with a rifle fire simunition at four officers, including him, in diamond formation. “When it was over, I said to myself: ‘Oh my God, I was very close to getting shot in the guts’. That shook me a little bit. My doctor said we probably shouldn’t do that again,” he said.

Barrett said he hopes he can “close the door” on October 22nd after the 10th anniversary.

But he said there are positives to be gleaned from his experience.

“It is possible to overcome PTSD and the RCMP has taken steps to make things better for the next generation of members,” he said.

When I wrote about this story in 2016, I called Barrett, Canada’s loneliest hero. He’s not lonely anymore. But both he and Kevin Vickers are in danger of being Canada’s forgotten heroes.

That can’t be allowed to happen. Both represent the very best values of this country - self-sacrifice and service to something bigger than themselves.

Lest we forget.

He’s doing so well, he’s a sergeant now and he retires on full pension in four years!

Wonderfully written, John. I had no idea. God bless them both.