A tropical take on haggis, bagpipes and Robert Burns

A tribute dinner to Scotland's poet comes to Costa Rica - but what's all the fuss about?

For the sake of my own mental health, I’m taking a break from Donald Trump to focus on another, more laudable, son of a Scots mother - the poet, Robert Burns, who was born on January 25th 1759.

The cult of Burns has gone global, even spreading to places where there appear to be no Scots. I haven’t met any in my 18 months in Costa Rica. That may be because the Caledonian constitution does not thrive in the Tropics. Scotland’s foray into colonialism started and ended with the disastrous Darien Scheme on the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s - most of the colonists died of tropical diseases; the venture all but bankrupted the country, and it lead directly to the hostile takeover by the perfidious English in 1707.

But let’s let bygones be bygones. The amiable British ambassador in Costa Rica, Ben Lyster-Binns, was convinced there was an audience for a Burns Supper and invited me to deliver the Address to the Haggis and the Immortal Memory to the poet. It turned out he was right. A good number of the country’s cabinet ministers turned out - drawn more by the free-flowing Highland Park, Macallan and Glenmorangie; by the delicious haggis made by British Master Chef Richard Neat; and by the excellent Costa Rican piper than by my ramblings on the “Great Chieftain o’ the Puddin-race”

But there was lively interest in Burns from a Tico audience more familiar with the Scotland portrayed in the TV show, Outlander, than that of the proto-Romantic poet.

So what’s all the fuss about?

For many exiled sons and daughters of Scotland, Burns represents the soul of the country. This is probably why among non-religious figures only Queen Victoria and Christopher Columbus have had more statues raised in their honour around the world. The one pictured above is from my home town of Dumfries, in south-west Scotland, where Burns spent his final years and wrote some of his most well known poems. He died there in 1796, aged just 37.

The poet was born in 1759 in Alloway, Ayrshire, not too far from the great golf courses of Troon and Turnberry, now owned by one Donald J. Trump - that last mention, I promise, of a man Burns would likely have considered a “eunuch of the language”.

Burns was the eldest of seven children, the son of a self-educated tenant farmer. At the time, Scotland had one of the highest literacy rates in Europe because the Protestant church required its parishioners to be able to read the Bible for themselves.

His schooling was irregular but he was a bright boy and excelled at writing and history and was also proficient in mathematics, Latin and French.

Yet by 15, his education was over and he was forced into farming. His genius is that he was able to grow a crop of such enduring works from such small seeds.

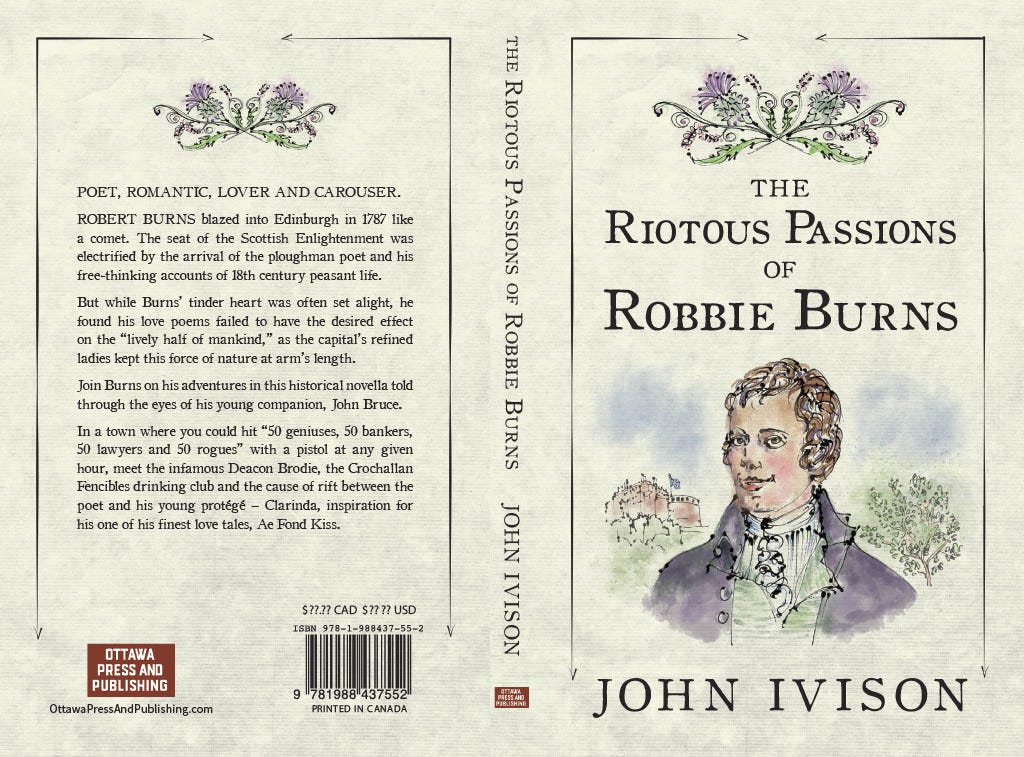

Burns was a charismatic figure, by all accounts: women wanted him and men wanted to be him. When he blazed into Edinburgh in 1787, he was received like a rock star by polite society. His time in Edinburgh was a tale in itself - one I tried to tell in my historical fiction, The Riotous Passions of Robbie Burns, which used the poet’s many existing letters as the basis for his dialogue.

Scotland’s greatest storyteller, Sir Walter Scott, met the poet as a 16-year-old and commented on his eyes:

“The eyes alone, I think, indicated the poetic character and temperament. They literally glowed when he spoke with feeling or interest. I never saw such another eye in a human head, though I have seen the most distinguished men of my time.”

The poet was a complicated man and a mass of contradictions. He was also rude, crude and funny.

Take the errant hero of his narrative masterpiece, Tam O'Shanter, whom we first encounter boozing in a cozy pub, not thinking of the long miles between him and home, "where sits our sulky, sullen dame; gathering her brows like gathering storm; nursing her wrath to keep it warm."

But he also had a tender heart. Sitting in church with the family of a friend in the Borders, he noticed a girl agitated by a sermon dwelling on hellfire. Burns took her bible and inscribed:

“Fair maid, you need not take the hint/ Nor idle text pursue/ ’Twas only sinners that he meant/ Not angels such as you.”

As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. Auld Lang Syne, sung around the world on Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and Scots Wha Hae, for a long time used as an unofficial national anthem of the country, are two such examples.

Burns did all this as a kind of poorly paid side gig. He literally worked himself to death as a farmer and tax collector, exposing himself to the worst of the Scottish weather in all seasons.

He had constant financial problems yet he rarely accepted money for writing poetry. He said he would “as soon think of offering a fee to a thrush singing in a thorn-bush. My bardship is a force as natural as the trout swimming in the river. It can’t be bought and sold.”

Even his politics were complicated, given he was torn between his republican sympathies and his need to keep in the good graces of the authority figures he relied upon for employment. He once bought four small cannons from a smuggling schooner he had helped to capture near Dumfries and shipped them off to revolutionary France.

He was forced to make amends by penning the patriotic poem Dumfries Volunteers - and by joining the regiment of the same name - to keep his government bosses happy.

He was certainly flawed but as his friend Maria Riddell wrote in his obituary: “It is only on the gem that we see the dust. The pebble may be soiled and we never regard it.”

He died on 21 July 1796, the same day his son Maxwell was born, and the cult of Scotland’s darling was born. Uniformed soldiers lined the streets to St. Michael’s Churchyard, where he is buried, the town’s bells tolled and a cavalry band played Handel’s Dead March.

This history was all around me growing up but familiarity bred contempt, rather than adoration. Burns was a long dead poet whose work we were force-fed at school.

Ae Fond Kiss was considered to be the “essence of a thousand love tales” by Sir Walter Scott, but it was lost on my insensitive soul, even if it was written upstairs from where I used to get my hair cut.

As a young man, my friends and I would wander past the churchyard where he is buried and past his two-storey sandstone house, where he penned poems like A Man’s a Man for A’That, en route to the Globe Inn, his favourite drinking establishment, which is still doing a roaring trade today. He spent many hours there, drinking claret, gazing into the fire and seducing the barmaids. We were oblivious to the fact that the poet had engraved a stanza to honour a barmaid of his acquaintance in a window upstairs. You can still read it to this day:

“O lovely Polly Stewart, O charming Polly Stewart/ There’s ne’er a flower that blooms in May/ That’s half as fair as thou art”.

Age and distance offered perspective. It was only after I moved to Canada in the ‘90s that I really began to appreciate my home town’s self-taught poetic genius.

And it was only after delving deeper I began to appreciate that Burns was a pioneer - championing liberalism in a time of intolerance; republicanism in the age of monarchy; secularism, when religious superstition still dominated life; and romanticism, long before Wordsworth, Coleridge or Shelley, on whom he was a great influence.

As an aside, his impact reached well into the 20th century through writers like John Steinbeck - the title of his book Of Mice and Men comes from Burns’ poem To a Mouse; JD Salinger, who’s novel Catcher in the Rye plays on the themes of Burns’ Comin’ Through the Rye; and Bob Dylan, who chose My Luve is Like a Red, Red Rose as the verse that had the greatest impact on his life.

From far away, his poems gained extra poignancy, because they talked about places I knew and issues I cared about, in a language I could understand.

Some years ago, I was in Dumfries and wandered with my Dad along the River Nith, at Ellisland Farm, where Burns wrote Tam O’Shanter. This was the river that Burns said was the midwife to many of his creations

Walking in the Bard’s footsteps offered an incredible connection to him for both of us. Just like Tam O’Shanter, drinking and telling stories with his friends in front of the fire, the moment was transcendental.

“Bees flew home with lades of treasure/ The minutes winged their way with pleasure/ Kings may be blessed, but we were glorious/ Over all the ills of life victorious”.

My father has since passed on, but that is a treasured memory for me, recalling my sense of pride in my family, my hometown and in Burns.

The poet may have died young but he left a rich legacy of beautiful and powerful verse.

If you have a glass handy, I would urge you to fill it with a good Scotch and drink a toast to the Immortal Memory of Robert Burns.

Wonderful insight to the bard of whom I knew not.

Slàinte mhòr!